Understanding Life-Cycle Cost Analysis; Why Projects Must Have One

Nationwide Consulting, LLC Explains the Basics of Life-Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA)

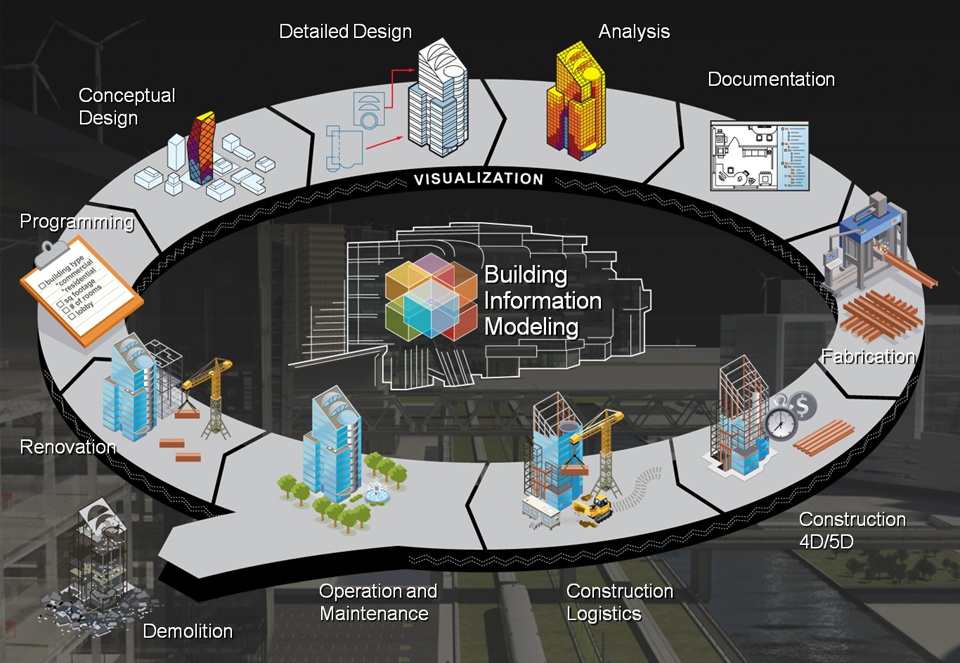

Life-cycle cost analysis (LCCA) is a method for assessing the total cost of facility ownership. It takes into account all costs of acquiring, owning, and disposing of a building or building system. LCCA is especially useful when project alternatives that fulfill the same performance requirements, but differ with respect to initial costs and operating costs, have to be compared in order to select the one that maximizes net savings.

For example, LCCA will help determine whether the incorporation of a high-performance HVAC or glazing system, which may increase initial cost but result in dramatically reduced operating and maintenance costs, is cost-effective or not. LCCA is not useful for budget allocation.

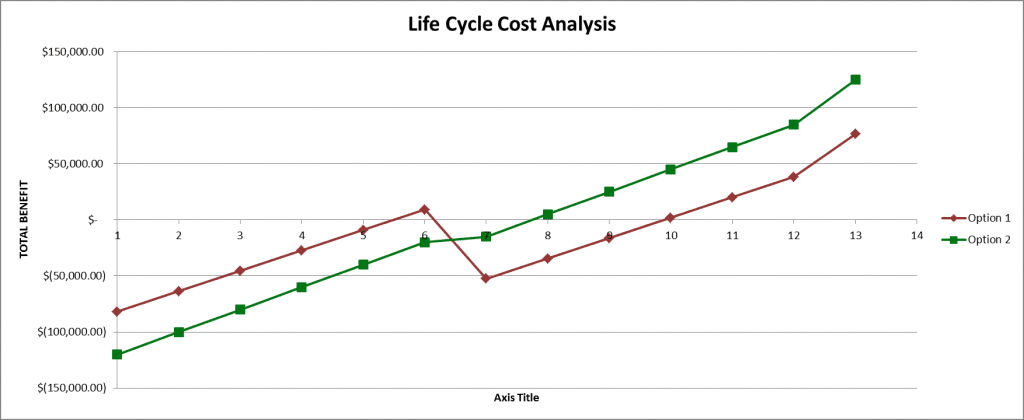

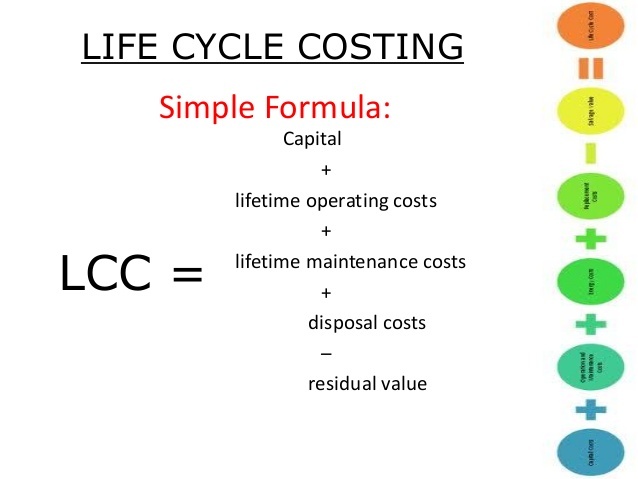

Lowest life-cycle cost (LCC) is the most straight forward and easy-to-interpret measure of economic evaluation. Some other commonly used measures are Net Savings (or Net Benefits), Savings-to-Investment Ratio (or Savings Benefit-to-Cost Ratio), Internal Rate of Return, and Payback Period. They are consistent with the Lowest LCC measure of evaluation if they use the same parameters and length of study period.

Building economists, certified value specialists, cost engineers, architects, quantity surveyors, operations researchers, and others might use any or several of these techniques to evaluate a project. The approach to making cost-effective choices for building-related projects can be quite similar whether it is called cost estimating, value engineering, or economic analysis.

At Nationwide Consulting, LLC it is our job to sort through all data provided to give precise reporting and evaluations. This gives owners an LCCA accurately representing data they can understand in one concise report.

Life-Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) Method

Life-Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) Method

The purpose of an LCCA is to estimate the overall costs of project alternatives and to select the design that ensures the facility will provide the lowest overall cost of ownership consistent with its quality and function. The LCCA should be performed early in the design process while there is still a chance to refine the design to ensure a reduction in life-cycle costs (LCC).

The first and most challenging task of an LCCA, or any economic evaluation method, is to determine the economic effects of alternative designs of buildings and building systems and to quantify these effects and express them in dollar amounts.

Take for example, a comparison of the cost of a physical building as compared to the workforce that will occupy it and maintain it over the years. The design and construction costs are at 2% of the cost, maintenance costs are at 6% and personnel salaries are at 92%. Viewed over a 30 year period, initial building costs account for approximately just 2% of the total, while operations and maintenance costs equal 6%, and personnel costs equal 92%.

Viewed like this, under LCCA reporting, would an increase in initial construction costs that may reduce personnel cost and efficiency be of more interest?

Costs

There are numerous costs associated with acquiring, operating, maintaining, and disposing of a building or building system. Building-related costs usually fall into the following categories:

- Initial Costs—Purchase, Acquisition, Construction Costs

- Fuel Costs

- Operation, Maintenance, and Repair Costs

- Replacement Costs

- Residual Values—Resale or Salvage Values or Disposal Costs

- Finance Charges—Loan Interest Payments

- Non-Monetary Benefits or Costs

Only those costs within each category that are relevant to the decision and significant in amount are needed to make a valid investment decision. Costs are relevant when they are different for one alternative compared with another; costs are significant when they are large enough to make a credible difference in the LCC of a project alternative. All costs are entered as base-year amounts in today’s dollars; the LCCA method escalates all amounts to their future year of occurrence and discounts them back to the base date to convert them to present values.

Initial costs

Initial costs may include capital investment costs for land acquisition, construction, or renovation and for the equipment needed to operate a facility.

Land acquisition costs need to be included in the initial cost estimate if they differ among design alternatives. This would be the case, for example, when comparing the cost of renovating an existing facility with new construction on purchased land.

Construction costs: Detailed estimates of construction costs are not necessary for preliminary economic analyses of alternative building designs or systems. Such estimates are usually not available until the design is quite advanced and the opportunity for cost-reducing design changes has been missed. LCCA can be repeated throughout the design process if more detailed cost information becomes available. Initially, construction costs are estimated by reference to historical data from similar facilities.

Alternately, they can be determined from government or private-sector cost estimating guides and databases. The Tri-Services Parametric Estimating System (TPES) contained in the National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS) Construction Criteria Base (CCB) developed models of different facility types by determining the critical cost parameters (i.e., number of floors, area and volume, perimeter length) and relating these values through algebraic formulas to predict costs of a wide range of building systems, subsystems, and assemblies.

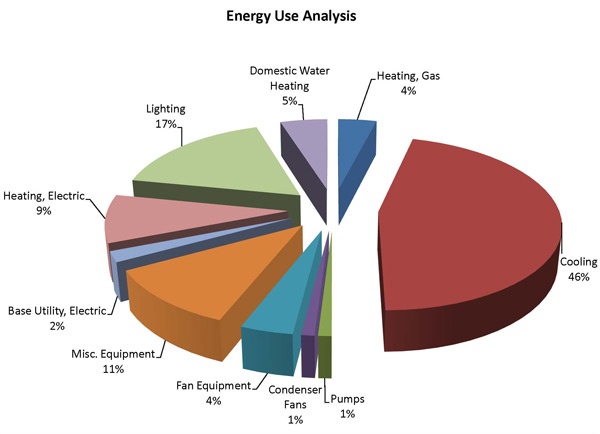

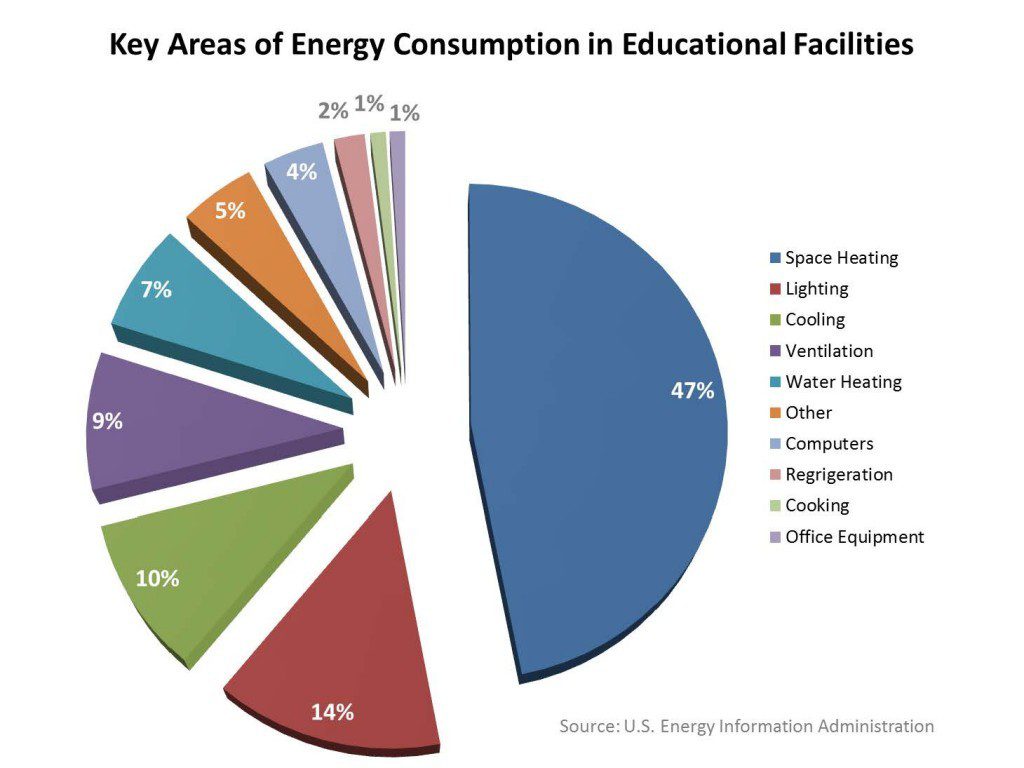

Energy and Water Costs

Operational expenses for energy, water, and other utilities are based on consumption, current rates, and price projections. Because energy, and to some extent water consumption, and building configuration and building envelope are interdependent, energy and water costs are usually assessed for the building as a whole rather than for individual building systems or components.

Operation, Maintenance, and Repair Costs

Non-fuel operating costs, and maintenance and repair (OM&R) costs are often more difficult to estimate than other building expenditures. Operating schedules and standards of maintenance vary from building to building; there is great variation in these costs even for buildings of the same type and age. It is therefore especially important to use engineering judgment when estimating these costs.

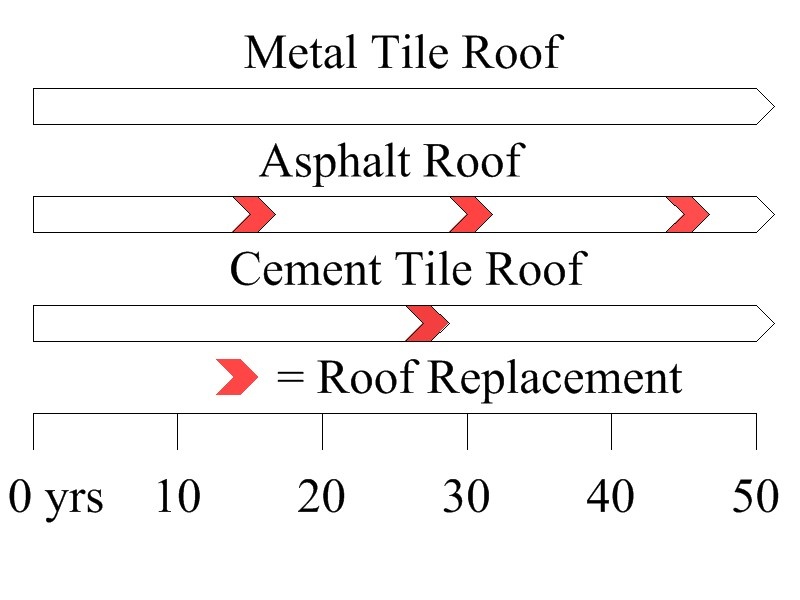

Replacement Costs

The number and timing of capital replacements of building systems depend on the estimated life of the system and the length of the study period. Use the same sources that provide cost estimates for initial investments to obtain estimates of replacement costs and expected useful lives. A good starting point for estimating future replacement costs is to use their cost as of the base date. The LCCA method will escalate base-year amounts to their future time of occurrence.

Residual Values

The residual value of a system (or component) is its remaining value at the end of the study period, or at the time it is replaced during the study period. Residual values can be based on value in place, resale value, salvage value, or scrap value, net of any selling, conversion, or disposal costs. As a rule of thumb, the residual value of a system with remaining useful life in place can be calculated by linearly prorating its initial costs. For example, for a system with an expected useful life of 15 years, which was installed 5 years before the end of the study period, the residual value would be approximately 2/3 (=(15-10)/15) of its initial cost.

Other Costs

Finance charges and taxes: For federal projects, finance charges are usually not relevant. Finance charges and other payments apply, however, if a project is financed through an Energy Savings Performance Contract (ESPC) or Utility Energy Services Contract (UESC). The finance charges are usually included in the contract payments negotiated with the Energy Service Company (ESCO) or the utility.

Non-monetary benefits or costs: Non-monetary benefits or costs are project-related effects for which there is no objective way of assigning a dollar value. Examples of non-monetary effects may be the benefit derived from a particularly quiet HVAC system or from an expected, but hard-to-quantify productivity gain due to improved lighting. By their nature, these effects are external to the LCCA, but if they are significant they should be considered in the final investment decision and included in the project documentation.

Parameters for Present-Value Analysis

Discount Rate

In order to be able to add and compare cash flows that are incurred at different times during the life cycle of a project, they have to be made time-equivalent. To make cash flows time-equivalent, the LCC method converts them to present values by discounting them to a common point in time, usually the base date. The interest rate used for discounting is a rate that reflects an investor’s opportunity cost of money over time, meaning that an investor wants to achieve a return at least as high as that of her next best investment. Hence, the discount rate represents the investor’s minimum acceptable rate of return.

The discount rate for federal energy and water conservation projects is determined annually by FEMP; for other federal projects, those not primarily concerned with energy or water conservation, the discount rate is determined by OMB. These discount rates are real discount rates, not including the general rate of inflation.

Cost Period(s)

Length of study period: The study period begins with the base date, the date to which all cash flows are discounted. The study period includes any planning/construction/implementation period and the service or occupancy period. The study period has to be the same for all alternatives considered.

Service period: The service period begins when the completed building is occupied or when a system is taken into service. This is the period over which operational costs and benefits are evaluated. In FEMP analyses, the service period is limited to 40 years.

Contract period: The contract period in ESPC and UESC projects lies within the study period. It starts when the project is formally accepted, energy savings begin to accrue, and contract payments begin to be due. The contract period generally ends when the loan is paid off.

Discounting Convention

In OMB and FEMP studies, all annually recurring cash flows (e.g., operational costs) are discounted from the end of the year in which they are incurred; in MILCON studies they are discounted from the middle of the year. All single amounts (e.g., replacement costs, residual values) are discounted from their dates of occurrence.

Treatment of Inflation

An LCCA can be performed in constant dollars or current dollars. Constant-dollar analyses exclude the rate of general inflation, and current-dollar analyses include the rate of general inflation in all dollar amounts, discount rates, and price escalation rates. Both types of calculation result in identical present-value life-cycle costs.

Constant-dollar analysis is recommended for all federal projects, except for projects financed by the private sector (ESPC, UESC). The constant-dollar method has the advantage of not requiring an estimate of the rate of inflation for the years in the study period. Alternative financing studies are usually performed in current dollars if the analyst wants to compare contract payments with actual operational or energy cost savings from year to year.

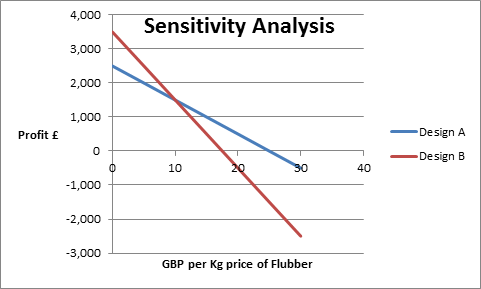

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis is the technique recommended for energy and water conservation projects by FEMP. Sensitivity analysis is useful for:

- Identifying which of a number of uncertain input values has the greatest impact on a specific measure of economic evaluation,

- Determining how variability in the input value affects the range of a measure of economic evaluation, and

- Testing different scenarios to answer “what if” questions.

To identify critical parameters, arrive at estimates of upper and lower bounds, or answer “what if” questions, simply change the value of each input up or down, holding all others constant, and recalculate the economic measure to be tested.

Break-even Analysis

Decision-makers sometimes want to know the maximum cost of an input that will allow the project to still break even, or conversely, what minimum benefit a project can produce and still cover the cost of the investment.

To perform a break-even analysis, benefits and costs are set equal, all variables are specified, and the break-even variable is solved algebraically.

When it has to be done right, hit the Expert Button

Call Nationwide Consulting, LLC today for a free consultation and you hit the expert button:

Nationwide Consulting, LLC

Robert E. Hanson

Principal Partner

410.336.4961